1.The Curtius Palace and Residence

“Although it is a building owned by a private individual, the Curtius house deserves to be counted among the most beautiful in Europe” wrote Philippe de Hurges in 1615. He was coming from Tournai, en route to Cologne.

The Curtius Palace, which gave the museum its name, is the most emblematic building on the site. It owes its name to one of the richest people in the city, Jean de Corte (1551–1628), who Latinised his name to Jean Curtius.

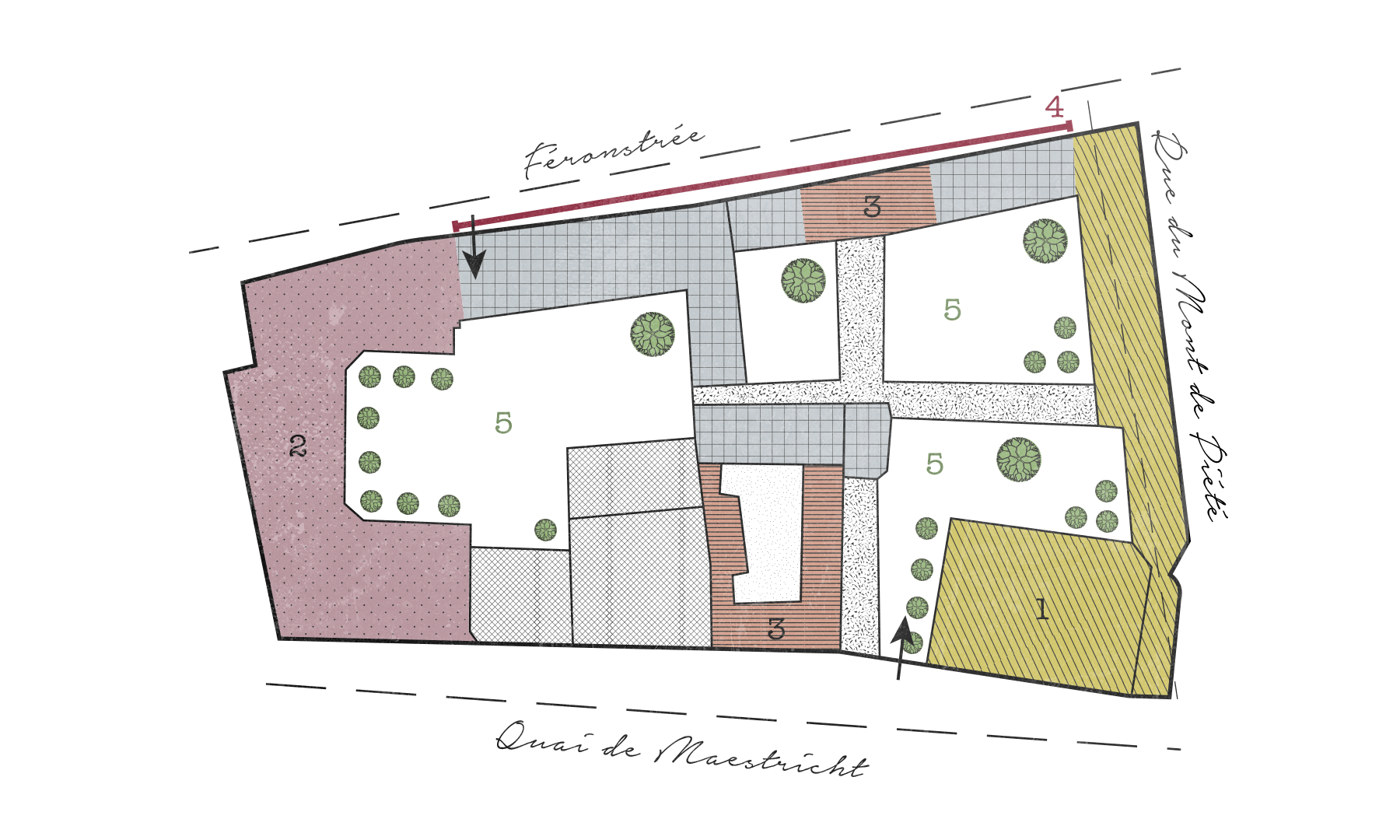

At the time, the building was part of a very important architectural complex that included, besides the "palace", which served as a guest house and store, the family’s residence, located in Féronstrée, as well as numerous common ones where one could find housing for the servants, stables, a gallery and a garden, the splendour and opulence of which were already well-known in the 17th century.

This complex was built on the site of an old canonical house of St. Bartholomew, which Jean Curtius had acquired in 1592. The works, which were started in 1597, were completed around 1603–1604, as attested by the dates inscribed in the interior fireplace decorations on the first floor.

Upon the death of Jean Curtius in 1628, the property was split in two: on the one hand, the “palace”, which was transferred to the Mont de Piété and, on the other hand, the residence, which remained with the family until 1734.

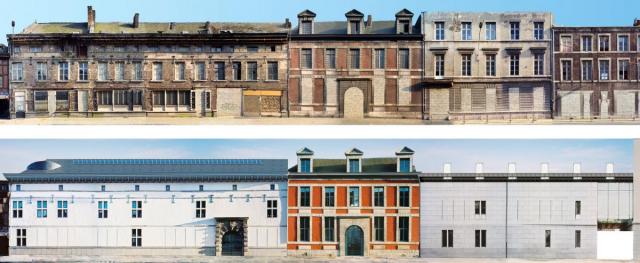

After passing through different hands, the two entities were bought by the city of Liège, the first in 1902 and the second in 1921, so that it could be reconstituted some three hundred years after his death. In the meantime, between 1904 and 1909, the “palace” was restored by the architect Lousberg, who reconstructed the tower in full. This building is characteristic of Mosan architecture from the 17th century, with its casement windows made from calcareous stone and bricks, which are found under a richly decorated and gilded slate roof. The mascarons that adorn the façade add decorative and symbolic elements to the magnificence of the interior decorations. Depicting blazons, fantastic animals and religious or satyric scenes, these mascarons, which were sculpted in Mosan freestone, have recovered their original polychromy during the restoration by the architects Lesage and Satin in 2001.

Jean Curtius: a fortune that was more than smoke and mirrors

Jean de Corte, who was known as Curtius, was a Liège industrialist who, thanks to the sale of arms and saltpetre, managed to accumulate a considerable fortune.

Coming from a family of Brabant origin, Jean de Corte inherited, through his marriage with Pétronille de Braaz, the daughter of a wealthy Liège merchant, various properties, including the chateau in Waleffe, close to Liège. He was also the owner or lord of twelve lands, including those of Tilleur, Hermée, Oupeye and Vivegnis.

It was around the coal mine and the powder factory that he owned at Chaudfontaine that the industrialist built his career. In 1595, he purchased a mill in the same region – the Curtius mill – with the intention of turning it into a large complex for the production of gunpowder. There, he notably constructed a wall and raised a casemate with its staves.

In 1605, he acquired the island of Ster, which was formed by the canal and the Vesdre river. On the banks of the Meuse, he built other mills, forges and rolling mills.

Named "General war commissioner" during the reigns of Philip II and Philip III, Jean Curtius gradually built a fortune thanks to the sale of gunpowder, which he had a monopoly on for the Spanish army. It is this money that allowed him to acquire the Oupeye and Grand Aaz chateaux and his own home, in Liège, which would become the present-day Curtius Museum.

When Spain made peace with her two powerful enemies, France and England, and then with the United Provinces during the "Twelve Years' Truce" (1609), Jean Curtius’ business declined. He then moved to Spain and, in 1617, settled in Cantabria, in Liérganes, where he built a forge and worked in the installations in Liège.

The significant expenses he then incurred, and the reduced return from his Liège companies, forced him to sell his rights to his Lierganes businesses in 1628, a little before his death in an inn in the city. In the years that followed, the Lierganes forge began to flourish and then became one of the most important.